Peter Berg

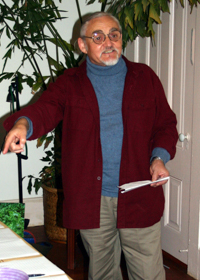

Interview by David Zane Mairowitz, 2007

Contents

Introduction

David Zane Mairowitz has authored numerous books that look at

avant-garde culture. He was living in Berlin when this interview took

place. He and

Peter Berg had never met although Mairowitz had been in

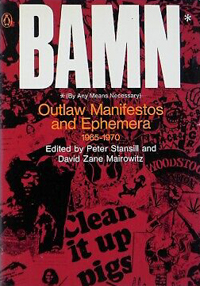

San Francisco during 1967. In one of his first books, titled BAMN (by

Any Means Necessary): Outlaw Manifestos and Ephemera, 1965-70,

Mairowitz had included reprints of several Digger and Free City street

sheets. Berg was impressed by Mairowitz’s compilation of underground

manifestos and recommended it to anyone in the early 1970s who asked

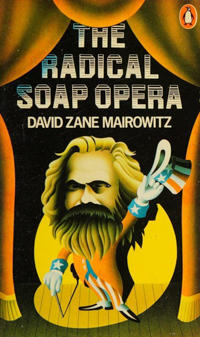

about the Digger movement. After BAMN, Mairowitz wrote Radical Soap

Opera which included his synopsis of the Diggers.

This interview took place by phone in 2007. Mairowitz was working on a

project around the events of May 1968. He explained to Berg that the

interview would be done in the present tense, as if they were speaking

in 1968 about the events taking place in the United States and worldwide

at the time.

Synopsis

Peter Berg, director of the

Planet Drum Foundation, discussed his time with the Diggers.

Berg explained the Diggers' origins in the San Francisco Mime

Troupe, their embrace of provocative tactics like the "Free Store"

and the "1% Free" poster, and their dedication to providing free

services and promoting individual expression as a form of social

change. He contrasted the Diggers' approach with its emphasis on

individual creativity with the more confrontational tactics of

groups like the Motherfuckers. Berg argued that the Diggers' legacy

lived on in movements for social justice and environmentalism, and

he discussed Free City, a 1968 Digger project that extended their

message citywide through events like the occupation of San Francisco

City Hall steps.

Topics Discussed

- Introduction to Peter Berg and Planet Drum

Foundation: Berg’s role as director of an ecological

activist and educational organization focused on promoting

bioregionalism.

- The State of the Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s:

Descriptions of Haight-Ashbury as a hub of countercultural

activity, its secession-like status from the rest of San

Francisco, and the police repression that followed.

- The Digger Movement's Origins and Philosophy:

Discussion of the Diggers’ inspiration from the 17th-century

English Diggers, the San Francisco Digger principle of

“everything is free, do your own thing,” and the emphasis on

anti-materialism and individual freedom.

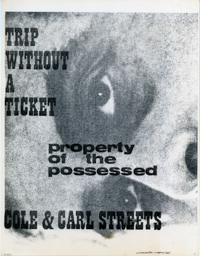

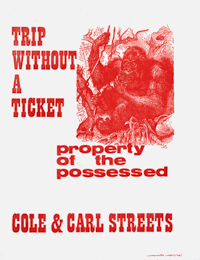

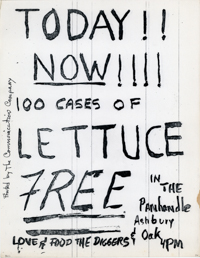

- Digger Free Services: The Diggers'

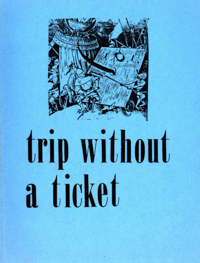

projects like the Free Store (“Trip Without a Ticket”), Free

Food programs, and how these initiatives met the needs of the

youth coming to San Francisco.

- The Diggers' Theatrical Approach: How

the Diggers emerged from the San Francisco Mime Troupe and used

Life Acting as a form of social-political theater, transforming

everyday life into a form of participatory theater.

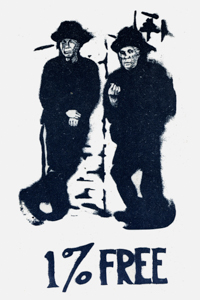

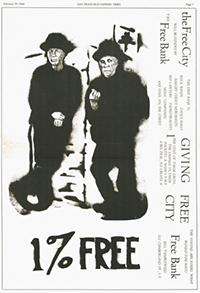

- The "1% Free" Poster: Discussion

about the creation, meaning, and impact of the “1% Free” poster,

symbolizing the provocative and thought-provoking nature of

Digger messaging.

- Free Bank and Free Economy Concepts:

The idea of a Free Bank, how it was enacted in practice (e.g.,

distributing money on the streets), and how this challenged

conventional notions of economy and ownership.

- Differences Between Diggers and Other Radical

Groups: Comparisons between the Diggers and other

anarchist groups like the Motherfuckers, highlighting the

Diggers' emphasis on proactive creativity and community versus

violent protest.

- The Transition to the Free City Collective

(1968): The shift from the Diggers to the Free City

Collective, focusing on occupying City Hall steps and expanding

their activities to other neighborhoods in response to police

repression.

- Impact of the Diggers and Their Legacy:

Berg’s reflections on the influence of the Digger movement on

future social, political, and ecological movements, and how

their spirit lives on in ideas of mutualism and interdependence.

- Anonymity and Collective Action: The

importance of anonymity within the Diggers' work, serving both

as a form of resistance to police surveillance and as a means of

promoting mutuality and interdependence.

- The Digger Film "Nowsreal": A brief

mention of the film documenting the Diggers and their

activities, made anonymously to maintain the spirit of the

movement.

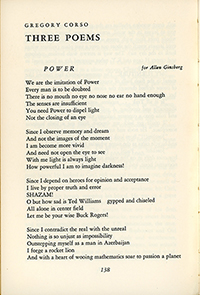

- The Slogan “Today is the first day in the rest

of your life”: Discussion about the meaning and origin

of this slogan, its connection to beat poet Gregory Corso, and

its relevance following the assassination of Martin Luther King

Jr.

- Connections with Other Key Figures and

Movements: Mention of Ronnie Davis, co-founder of the

San Francisco Mime Troupe, and Berg’s encounters with other

influential radicals like Abbie Hoffman and the Situationniste

in France.

The Planet Drum Foundation website has a slightly differently edited version of

this interview, along with an audio file:

here.

The Interview

Interview of Peter Berg by David Zane Mairowitz

October 2007 (via phone)

[Legend | PB: Peter Berg | DM: David Zane Mairowitz]

DM: Peter, what I would like to start with is — would you just tell me

who you are, and what you basically do in life, and so on.

PB: My name is Peter Berg. I'm director of

Planet Drum Foundation, which

is an ecological activist and educational organization. We promote the

idea of bioregions throughout the planet.

DM: Going back into the present tense, what's going on in May 1968,

what's going on in the streets of San Francisco? Tell me what's going on

in the streets outside.

PB: Since late fall in 1967, the police have changed the traffic

patterns so that Haight Street is now a one-way street. They've

installed sort of yellow, yellowish mercury-vapor lights that burn all

night. And they run patrol cars and paddy wagons up and down the street

about every half hour. They're picking up anyone who looks underage or

anyone who they want to pick up to check for identification. Because of

that, they're arresting about 20 people every half hour.

DM: Why are they doing that? What's the problem?

PB: During 1967, the neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury essentially seceded

from the City of San Francisco. If we had had our own water, sewage, and

electricity, we would have been a separate city. It was a little like

the taking of the heights of Paris by the

Paris Commune in the late 19th

century in France.

DM: I've heard a lot about this Haight-Ashbury. What is that whole area?

What's that all about? Can you tell me?

PB: The Haight-Ashbury is the neighborhood in San Francisco that was

first brought to national attention for being the most highly racially

integrated neighborhood. And it was the site in the middle 1960s of the

stopping of freeway expansion. Freeway is the American term for

expressways. One was planned for the middle of this neighborhood. And

the neighborhood and other organizations in the city rejected it. So, it

was the stopping of the freeway expansion, traffic expansion, in the

city — which, by the way now, is very advanced. Freeways are being taken

down in San Francisco now. But then, the stopping of a freeway was a

major social protest. And from that, from those two roots — being

fertile for social protest and being highly racially integrated — the

Haight-Ashbury became a desirable site for the same trend in population

that created North Beach as a beatnik haven in the 1950s. The

Haight-Ashbury became a haven for alternative lifestyle and rebellious

elements in San Francisco. From 1965 through 1967, this increased to the

point that the neighborhood, in terms of population and expansion and

governance — became its own social, political, cultural entity, and the

city simply couldn't stand it. So, the police reacted by trying to stop

the social upheaval that was happening there.

DM: Okay. But what interests us mostly — because that's really the kind

of starting point of Digger — is what the press ridiculously refers to

as the Summer of Love, and so on. But there was a huge run on the city

of San Francisco, especially in Haight-Ashbury in 1967. And we are in

1968. So, what happened there last year?

PB: Oh, it was the crescendo of the alternative culture rebellion in the

United States, throughout the United States, and I believe, Western

industrialized culture. The 1967 period in the Haight-Ashbury was a

triumph of opposition to war; putting forth of more-human values, values

associated with nature; love between human beings; creativity;

expression of individuals; and a disavowal of racism, militarism and

oppression that had been associated with industrial culture. The Diggers

took a particular slant on all of that, basing their philosophy on the

Diggers in England in the 17th century, who reacted to the Enclosure

movement which took land away from agriculturally productive peasants

and turned it into massive sheep farming. Taking their name from that

group, they declared Golden Gate Park and the Panhandle — an extension

of the park that runs through the Haight-Ashbury — as a kind of commons;

and declared, as the Diggers in England had, that everything should be

free and replaced the Protestant ethic of the Diggers with an ethic that

one should do one's own thing. So, the motto of the Diggers was,

“everything is free, do your own thing.” And the goal of the Diggers was

to provide free services and free culture that would inculcate those

values into the people that were streaming into the Haight-Ashbury, at

the rate of about a hundred thousand a year.

DM: So, there is actually a kind of social crisis going on, in the sense

that you've got all these young kids who have descended on the city.

There's nowhere for a lot of them to stay, a lot of them are going

hungry, there is a drug problem. So, what are the Diggers doing about

this?

PB: Well, I think the way you're stating it is the way the Establishment

stated it.

DM: Okay; contradict me.

PB: We saw them as refugees from mainstream America — that mainstream

America, and, by the way, a lot of these people were from other

countries as well, was breaking down. It was not fulfilling the dreams,

aspirations, or hopes of this younger generation. Instead of peace,

love, joy, productivity, creativity, they were being offered war, death,

a money economy, a life of servitude in jobs — rather than a promise of

fulfilling their hearts and their spirits. So, they flocked to the place

where they thought that could be done.

DM: And, what is the response, then, of a group like Digger to their

needs? What are the concrete things that are being done about this?

PB: The foundation of the Diggers was in a radical theater group that

was called the

San Francisco Mime Troupe. It still exists in San

Francisco, and it's associated with Left radical politics and causes.

But approximately 35 or 40 of the members of the Mime Troupe at that

time defected from doing the free theater in the park that we had been

doing, and began seeing the population, the Haight-Ashbury, as an

audience for a new formulation of social-political ideals that we

thought were an adequate response to oppressive American society at that

time. So “do your own thing, everything is free” took the form of

providing free food, free shelter, free cultural events, and an

opportunity to join in, and participate, with this kind of lifestyle,

which we called Life Acting. So, the root basis is theater. And if you

want me to answer, what did we give the people, we gave them

participation in a life theater of acting out a political, cultural,

social ideal. And they did that. They did it willingly and joyfully. Our

events in the park had up to ten thousand people. And [we] designed

events for the street that involved the participation of at least five

thousand people — in the middle of Haight Street.

DM: Can you tell me a little bit more about things like the free store,

and the idea — even though this may be a myth — the idea of money being

handed out on the streets, and the whole notion of "Free."

PB: Well, all of that was, and is, obviously symbolic. The

Free Store

was the epitome of a theater, a participatory theater. First of all, you

tell someone it's a store, and that everything in it is free. All right.

And then, the name of it was Trip Without a Ticket. It meant you should

indulge in a journey that won't cost you anything. Within the store

there were goods. The goods were provided by neighbors and people that

had surplus. And every morning, we would find a pile of goods on the

sidewalk outside the store; open it; ask volunteers to put it on the

shelves; and up to a hundred thousand people that were in the streets of

the Haight-Ashbury would come streaming in to find clothes, toys,

objects. I think the first LED digital clock I ever saw was given to the

Free Store by someone from Silicon Valley. We made jewelry out of

printed circuits from computers. We did the first tie-dyeing in the

Haight-Ashbury, on the floor in the Free Store, because nobody would

wear the white shirts that were being donated to us by people that

didn't want to work in offices anymore; so, we decided to tie-dye to

make them useful. And people learned how to dye them. So there — the

whole ideology is right there. Everything is free; do your own thing;

participate, and create something expressive; and join and expand this

idea.

DM: What about the myth — maybe it's the truth, you can tell me now —

that a lot of these free goods — as they used to say in England — fell

off the back of a truck?

PB: Oh, very few of them. Most of it was donated. Even the free food

that we served in the park was either yesterday's produce, from the

central [produce] market that the vendors were going to throw away

anyway; or onions and potatoes and field crops that we went out and

gleaned in large trucks and brought back into the city.

Digger Stew was

the staple food we served, and it was essentially a vegetable stew, made

in a milk can —gallons of it at a time — heated from the outside, from

the bottom, by a fire. And we'd just put in whatever vegetables we had

gotten that day.

DM: And what about, you know, I still — believe it or not, after 40

years, it's the only thing that I ever keep with me wherever I go — I

still have the original poster, “1% Free.”

PB: The two Tong men leaning against the wall? I designed that poster.

DM: Okay. Now, I know what it is, but people listening won't know. So,

could you describe to us the poster, and then tell me a little bit about

the idea of 1% Free?

PB: The

poster is a reproduction of a photo that was done during the

first notable earthquake — the ought-six earthquake in San Francisco —

of two Chinese Tong men, who were the enforcers for the Chinese gangs in

the city. The two Tong men are leaning against a wall, in Chinatown.

It's large, at least five feet high and three-feet-plus across. It's

been spray-painted onto a stencil, so that it has a rough blue-jean,

blue-denim look to it. The faces and the hands of the Tong men were made

on a Xerox machine [correction: Gestetner mimeograph], and then cut out, and pasted onto the surface, so

that it has a ghostly three-dimensional look. And at the top is the

Chinese character for molting, or revolution. It's the symbol for

transformation. And at the bottom is the slogan "1% Free." And this was

printed onto newsprint — which is the same material that the newspaper

is made out of — and glued with flour-paste glue onto banks, freeway

stanchions, the outside of the walls of grocery stores, throughout the Haight-Ashbury, and by the way, throughout neighborhoods of the city as

well. About a hundred and fifty of them were made, and very few of them

exist anymore in the large size. Several times they've been reproduced

in a smaller, conventional poster size; and even as cards. But of the

originals, there are very few left.

DM: And what does this mean, “1% Free”?

PB: Well, that's what everyone would [ask]. And I'm really proud to tell

you that just as the word "Diggers" provoked people to say, what do you

mean? That you understand things, that you dig them, or are you digging

something up, or whatever. It was meant to be provocative. And it's

taken from the Hells Angels shoulder patch on a Hells Angels motorcycle

club jacket that said "1%." Which meant, one percent of motorcycle

clubs. I took “1%” and then put "Free" after it, in the spirit of the

Diggers, to say roughly that only one-percent of the population was

capable of understanding or behaving in this way, at that time.

DM: Wasn't there also a project for a free bank, in which “1% Free”

played a role?

PB: Well interestingly, it was interpreted by the merchants on Haight

Street, who sold beads and candles and marijuana paraphernalia and hip

clothes; it was interpreted by them to mean that they should give one

percent of their money [laughs] to the Diggers, which I love. That's the

joy of a provocative title: it can evoke all kinds of responses. And

after that, by the way, one of those bead stores paid the rent on the

Free Store as a way of contributing their one percent. But it wasn't

meant for that; it was just meant as a provocation to the cultural

consciousness, especially of the psychedelic generation, to try to get

them to see beyond transcendental meditation into more social,

political, and long-term human goals.

DM: So, the idea of a

Free Bank is a total myth? It's something that I

just either invented or heard or whatever?

PB: We used to ask people, if they wanted to be a Digger, just put

"free" in front of some term that interested them, some activity or some

social institution — Free Food, Free

Store — and one of these people said he wanted to be a

Free Banker. So,

whenever people gave us contributions, we would give it to him, and he

would wear money in his hatband, and give it to anybody that asked him

for it as a demonstration of this kind, as a life act in the Theater of

Free, he would simply take the money out of his hatband, and hand it to

them.

DM: So, the Free Bank was actually a guy walking around with money in

his hat.

PB: That's right.

DM: Great.

PB: The same person drove a motorcycle down Haight Street and threw

coins out of a bag of money into the street, to all the people that were

panhandling. Because, you know, these refugees from America that were

showing up in the thousands had no employment. So, throwing money to

them was a way of supporting them for a little bit longer.

DM: And, how different is that, in your estimation, from, for example,

the famous case of Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies throwing dollar bills

from the New York Stock Exchange [visitor’s gallery] down below?

PB: Well, that was an imitation of what we were doing. They derived that

kind of activity from what we were doing. I was at the SDS meeting where

Abbie Hoffman first heard of the Diggers. I was the person that told him

about it. We were the Diggers who went to a meeting of SDS that turned

out to be their final meeting, where we told them that they should stop

doing what they were doing, and start a proactive revolutionary movement

that was based on alternative benefits; the benefits of an alternative

society, rather than protests at the old society.

DM: And how would you then — I mean, going back to our perspective of

'68, because this is the point of what I'm doing — you know, things are

exploding all over the globe in that particular year. There are so many

different movements, what's going on in France, what's going on in

different countries, and so on. How would you put Digger in that

perspective? What distinguishes Digger from all the rest of the things

going on in this year, 1968?

PB: Well, first of all, not all the Diggers were aware of what was

happening all over the world. I was aware of it. And I identified with

the

Situationniste in France, and the

Provos in the Netherlands; and

with the

Kommune people in Germany at the time, and I saw a thread of

continuity running through what we were doing. Because essentially, this

was a perpetuation of the anarchist philosophy of the 17th and 18th

century that has never died, and continues. And we were all exercising

different forms of it. It's a completely legitimate view of human

freedom. At the time of its inception in the 17th century, anarchism was

considered to be on the same par as democracy. Really a question of

where the ideals of freedom would go.

Jean Jacques Rousseau, who dates

from that period, is a founder of contemporary anarchism, and he put

anarchism and human freedom together with the way nature operates with

ecology, which is very contemporary. You know, our tradition was very,

is very contemporary. But it has roots that are firm roots in that same

soil.

DM: Okay, those are the connections. I mean –

PB: Yeah, those are the connections.

DM: – what, in your point of view, what is it about Digger that was

unique?

PB: I think the absolute individualism of it. The American political

spirit contains an individualistic streak that extends to expression and

creativity in many, many different ways. Americans tend to feel more

free about what kinds of things they're capable of doing, and to what

activities they might apply. This is my own observation, and someone

might feel that I'm wrong in this, but I think the Diggers, by saying

“everything is free, do your own thing,” were an expression of this

individualist, the importance of the individual in the social, in social

manifestation. In other words, that individual happiness and freedom was

a paramount goal of a social formulation.

DM: But, couldn't you say the same thing about a lot of anarchist

groups? I'm still, maybe I'm just insisting too much, but I'm still

looking for … because I was always very, very impressed by Digger, and

you know what I'm looking for here is that one particular thing that

sets Digger apart from all the other anarchist movements that one can

think of.

PB: Well, when the ideology really falls back on the individual, I think

that's what makes it different. That when you say, put "free" in front

of anything that you choose to manifest — and someone says, oh, okay,

I'm going to be the free taxi driver; I'm going to be the free banker;

I'm going to be the free parachutist; I'm going to be the free actor — I

mean, the ideology there is not what should we all do in common and in

lockstep, but the ideology is really what should we all do that will

result in a burst of fireworks; will burst out in ways that we don't

know yet. The unpredictability of that kind of individual application of

an ideology — I think that's what's distinct about the Diggers.

DM: And at the same time as Digger is happening in San Francisco, you've

got the

Motherfuckers in New York. If you had to say what the difference

would be between Digger and Motherfucker, what would you come up with?

PB: Well, uh, these days, the terms that are used are the difference

between protest and proactive. We were creative theater people; we

delighted in creating beautiful, sensual, expressive, participatory,

revelatory events. We believe that if you tripped somebody out; if you

gave them a fantasy fulfillment, or if they were able to feel empowered

to fulfill fantasies that were positive and socially beneficent; that

that was much more important than throwing a hand grenade at somebody

that you disagreed with.

DM: And did the Motherfuckers do that?

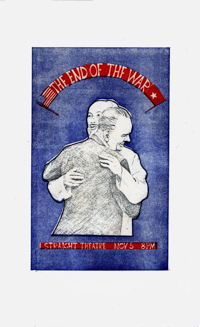

PB: Well, we had an event in San Francisco, it was called The End of the

War. It was done in late '67. We took over a theater, we had a free

theater performance. And we invited people to come and do the kinds of

things they would do if the war was over. The poster for that, by the

way, had Lyndon Johnson with his arms around Ho Chi Minh, and both of

them waving the other one's flag. And it said, "The end of the war." So,

some people performed nude dances. Some people carried around bows of

trees as sort of a sculptural theater presentation. And the

Motherfuckers' idea of what to do was to put up a table with different

kinds of ammunition. So, they put up a card table that had .38 bullets,

AK-47 bullets, just various kinds of bullets and different kinds of

Molotov cocktails.

DM: And what were they trying to do? What were they trying to say there?

PB: The Motherfucker idea was that if the war was over, the energy that

was being spent fighting the Vietnamese would be spent militarily

fighting the American government. Our view was that if the war was over,

and the energy that was being spent fighting the Vietnamese was

converted to another form, it would be creativity and transformation of

American society.

DM: Okay. What about the idea, as somebody said — maybe it's total

bullshit, from your point of view, that the Diggers were communists with

a small 'C"?

PB: Well, anarchism has always had an element of interdependence about

it; interdependence and mutualism. Interdependence and mutualism are the

kinds of forces that are so easily observed in nature. By the way,

that's one of the reasons why, when people ask me, whatever happened to

the spirit of the '60s, I say, well, it became the ecology movement.

Because that interdependence and mutualism is so evident in the way that

different organisms relate to each other; the roles that they have,

relative to each other. So, I think interdependence and mutualism exists

whether you enact them or not. If you enact them, you facilitate it, and

you stop destruction. If you don't enact mutualism and interdependence,

then you cause biological, biospheric, and human destruction.

DM: Do you think that Digger, the whole notion of Digger, ultimately

changed anything?

PB: Well, first of all, the opportunity to participate in the creation

of a modern form of the anarchist tradition was, and is, for me, an

extraordinary opportunity. So the Diggers don't have to do anything more

than what they've already done. In terms of what they represent now, I

know that young people are very interested in how to live a life that's

more fulfilling, more creative. In France, of course, it takes the form

of a shorter work week. When two women from Paris came, and wanted to

make a film about the Diggers some years ago —five years ago — I was

very helpful to them, because they introduced themselves as wanting to

provide a rationale for people who would work less. And even in Canada

today, there's a group called the Work Less Party. So, yeah, the Diggers

— “everything is free, do your own thing” — is wonderfully applicable to

the idea of people finding fulfillment in human creativity and

expression, rather than in robotically carrying out the ends of some

work regimen.

DM: Okay. Peter, one basically last thing, and then I think we've got

everything we need. I just, eh, am going to put some words that you know

into your head, and I'm gonna ask you to repeat them, so I don't have to

have them in my mouth, in the thing. So, you know, when you, when you

answer, please use the, the expression. What did the poster mean, or

what did the, the slogan mean, to you: Today is the first day in the

rest of your life?

PB: The first time I heard the phrase "Today is the first day in the

rest of your life," it came out of the mouth of the American beat poet

Gregory Corso. And it was in conversation. When he said it, I realized

that he had taken a simple revelation, and made it almost into … made it

into a credo. And the credo was — you are constantly beginning again.

And that's not in the tragic sense, of Sisyphus rolling the rock up on

the mountain again and again; but it's real, in the sense that life,

opportunity, consciousness, and perception are constantly changing, and

that that is a spirit to ally with, rather than to feel it's working

against you. So "Today is the first day in the rest of your life" is the

bright opportunity of starting over again, if one needs to, or one

should, or one does inevitably anyway; starting over again to recreate

the world around them. And I've always seen it as that.

DM: And why did it turn up on that poster the day of the assassination

of

Martin Luther King?

PB: Oh, because with the assassination of Martin Luther King, it was the

turning point. We saw it as the turning point in popular consciousness —

the final, absolute proof that American society had to change. If a

proponent of peaceful transformation would be killed violently, then it

was so obvious … it had to be obvious to everyone that the ideals of the

assassinated person should prevail in the end. So the verse actually

said, "Goodbye, Brother Martin. Today is the first day in the rest of

your life." It was addressed to everyone who was still alive.

DM: And I still have it, heh heh.

PB: Ha ha.

DM: Okay. Well, I just want to ask you a couple of personal, not

personal questions, but as you were talking, I was thinking of my old

friend Ronnie Davis. Is he still with us, or?

PB: He's still alive.

DM: Yeah? Is he still in San Francisco? What's he up to?

PB: He's still in San Francisco.

DM: Okay. Well, if you ever see him, give him my best. I would love to …

if you, if you ever have an email address for him, I would love to have

it. But uh, maybe I can find it some other way.

PB: Why don't you try Googling him?

DM: Yeah, I will do, will do. And, I'm also looking for a good

Motherfucker to be sort of your counterpart. I mean, have you got

anybody you could recommend to me, that you can think of?

PB: Well, an individual who is a source for that kind of information is

the Digger folk archivist in San Francisco, whose name is Eric Noble. Do

you know Eric Noble?

DM: I don't, no.

PB: He was, uh, as a teenager still, he was with the commune called

Kaliflower in San Francisco.

DM: And I can find him, I can Google him too, or, or have you got a, a –

PB: Eh, I'm about to find you a telephone number. Hold on.

DM: Okay.

PB: Uh, David –

DM: Yes?

PB: Eric is not eager to share information with media in general.

DM: Uh huh.

PB: He persists in the same suspicion that have about most of it. So –

DM: I will tell him who I am, and if it's not enough –

PB: You should identify yourself as the author of the Radical Soap Opera

–

DM: That's exactly what I will do, yeah.

PB: – and By Any Means Necessary, and also tell him that you were

referred by me.

DM: Okay.

PB: Uh, that's going to have some ability to open the door.

DM: Okay.

PB: I'm giving you a home number now. 415–xxx–xxxx.

DM: Okay.

PB: It's not his specialty, but I think he knows the general, uh,

territory.

DM: Um hm.

PB: The person that you should want to get hold of, of course, is [DAN

MARAYA].

DM: Yeah, I know, I know.

PB: But where or what's happened to Dan, I really don't know.

DM: I saw an interview with him a few years ago that somebody had done.

He seems quite willing to talk. But he's somewhere out in the West, you

know, and I don't know how to get to him. But I can, I can try and find

out. Well, I think that's about it, Peter, for the moment. If I need

anything more, we'll be in touch. I'm really pleased.

PB: You know, we left out something from 1968 that I'm disappointed

about.

DM: Do, do it, do it right now. We've still got plenty of time.

PB: In 1968 at the beginning of the year, we saw that with the

repression of the Haight-Ashbury by the police, which was intensive,

that our reaction should be to take the Digger spirit and put it in

other neighborhoods of the city, and on City Hall steps. So we occupied

City Hall steps, starting at the spring equinox — that would have been

March, mid-March — through the summer solstice, mid-June. We occupied

City Hall steps every day — reading poems, making proclamations, giving

away free food, bathing in the city fountain. It was a fixture. And it

was called Free City. So in 1968, the Diggers effectively changed their

focus of activity, and changed their name. Instead of the Diggers, they

became the Free City Collective and did events throughout the city, in

other neighborhoods — rock concerts, free-food events. But occupied City

Hall steps every day. That was our defiant response to what the city had

done. That was our '68; the year — the Digger style for the '68 period

was Free City and the occupation of City Hall steps.

DM: This is absolutely wonderful that you should bring that up, because

I actually have a film of that, which I found.

PB: Is it called

NOWSREAL?

DM: That's right, that's right –

PB: Yeah, we, that's my film. Uh, I made that film as a record of who we

were and what we did.

DM: Well, if you made that film, it's also very good news, because if I

use a piece of it, you probably get some royalties from it. So, {LAUGHS}

–

PB: Good, uh –the two people — the cameraman is

Kelly Hart.

DM: Yeah?

PB: And the director is Peter Berg.

DM: It's funny, because I didn't see that on the film. But in any case –

PB: Oh. That's because we were anonymous.

DM: Of course. Okay. Well, it's great, because it's good, it's good to

know, and because if I use it, they will surely ask me who needs to get

paid for that, and now I know. Heh.

PB: You know, you should mention somewhere — I think you should mention

it rather than me, because it would be a little hard for me to contrive

the opportunity right now — that everything the Diggers did was

anonymous. And the reason for anonymity was to impress people with this

notion of interdependence and mutuality. And it was a very good cover

for the police trying to track us down. So, you might mention it. You

might say that these things aren't authored; they don't have credits;

uh, the One Percent Free poster doesn't say "Peter Berg" on it; Nowsreal

doesn't say "Peter Berg" on it. The Free Store, the Trip Without a

Ticket manifesto, didn't say "Peter Berg" on it. And that was the

reason.

DM: Well, you just said it, and then you said it better than I could.

But in any case, the way I'm probably gonna present this is a kind of

interreaction of things like that.

PB: Good.

DM: So that's really great. Well look, Peter, it's, it's time. I've got

the, I've only got this studio for a [few] –

PB: I understand you're … you're in charge of a tremendous legacy,

David. I hope you –

DM: Heh. I know.

PB: – I wish you the best of luck with [it].

DM: I know it, and I will definitely let you know what it's going to be,

and send you –

PB: Okay.

DM: – the, the script, and uh –

PB: – I hope this turned out well.

DM: It did.

PB: Could you send me a tape?

DM: I will, ultimately, although you must realize, it's gonna be in

German. And you, and there will be –

PB: Ha ha ha ha!

DM: – be somebody voiceovering you …

PB: Okay.

DM: – ultimately. But, but I will leave you as much free space as I

possibly can.

PB: Good luck, David.

DM: All right, take care, thanks very much, Peter.

PB: Goodbye.

DM: Bye.

[End] —posted 2024-09-27

[Feel free to send any comments, additions,

corrections, &c. to the

curator of the Digger Archives]

|

[Click thumbnails once, click full version to return here]

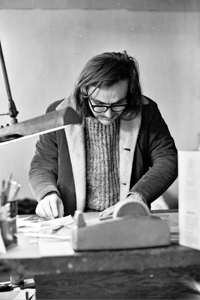

Peter Berg, 2006

David Zane Mairowitz

Peter handed David's book to me at the first Planet Drum bundle collating party in

1973.

Mairowitz included a chapter on the Diggers in this 1974 book.

The front-page SF Chronicle (11/30/66) photo of the five Diggers after "public

nuisance" charges were dropped stemming from the Intersection Game on Halloween

1966. Peter is fourth from the left.

"We occupied City Hall steps every day — reading poems, making proclamations,

giving away free food, bathing in the city fountain. It was a fixture. And it

was called Free City." (1968)

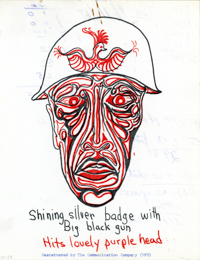

"We had an event in San Francisco, it was called The End of the War. It was done

in late '67. The poster for that, by the way, had Lyndon Johnson with his arms

around Ho Chi Minh, and both of them waving the other one's flag."

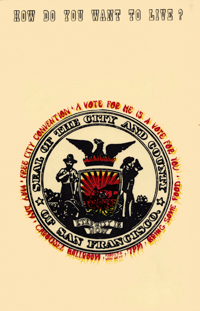

"How do you want to live" (poster announcing the Free City Convention, May 1,

1968, at the Carousel Ballroom)

"[The 1% Free poster] was interpreted by the merchants on Haight Street to mean

that they should give one percent of their money [laughs] to the Diggers, which

I love. That's the joy of a provocative title: it can evoke all kinds of

responses."

"[The 1% Free poster was] large, at least five feet high and three-feet-plus

across. It's been spray-painted onto a stencil, so that it has a rough

blue-jean, blue-denim look to it. The faces and the hands of the Tong men were

made on a [Gestetner mimeograph machine], and then cut out, and pasted onto the

surface, so that it has a ghostly three-dimensional look."

"The Digger style for the '68 period was Free City."

"The Diggers Are Not That" (a common refrain in the underground press)

One of the critical texts of the Digger movement, "Trip Without a Ticket"

written by Berg. (1966)

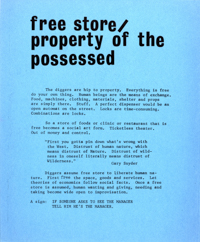

"Everything is free, do your own thing" (the motto that Berg and Grogan coined).

The second half of the phrase eventually entered the American lexicon.

"And [we] designed events for the street that involved the participation of at

least five thousand people — in the middle of Haight Street."

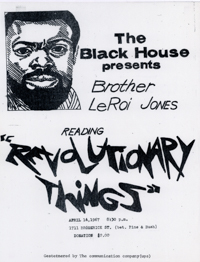

Communication Company street sheet announcing a reading by Leroi Jones (1967)

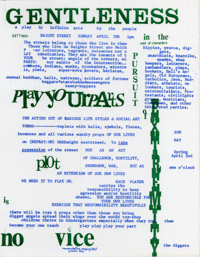

"Gentleness in the pursuit of extremity is no vice" (Digger manifesto on life

acting)

Communication Company street sheet announcing the third Digger free store.

"The police reacted by trying to stop the social upheaval that was happening

there." [in the Haight, 1967-68]

Another announcement for the Trip Without A Ticket free store. (1967)

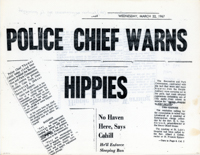

The City Establishment reacted in panic at the prospect of thousands of young

people coming to San Francisco in the summer of 1967.

A sign for Digger friendly homes to hand in the window.

"So 'do your own thing, everything is free' took the form of providing free

food, free shelter, free cultural events, and an opportunity to join in, and

participate, with this kind of lifestyle, which we called Life Acting."

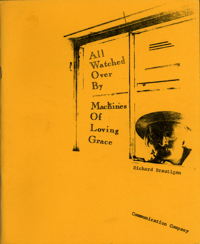

"All Watched Over By Machines of Loving Grace" a compilation of poems by Richard

Brautigan, given away free by the Communication Company. (1967)

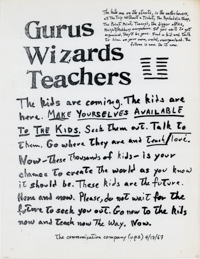

"Gurus Wizards Teacher" street sheet by Chester Anderson of the Communication

Company.

"A Moving Target Is Hard To Hit" by Lew Welch. (Com/Co street sheet, 1967)

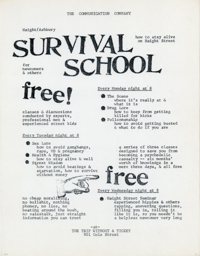

A series of free workshops at the Digger free store. (1967)

Peter Berg performing at one of the Free City "Noon Forever" events outside SF

City Hall. (1968) [Photo courtesy Chuck Gould]

Peter dancing pas de deux with Holy Hubert, the evangelical preacher who

regularly showed up to castigate the hippies and their evil ways. [Photo

courtesy Chuck Gould]

Judy Goldhaft and Peter Berg (longtime partners) [Photo courtesy Chuck Gould]

Peter working on the preparation of Free City News in the basement of Willard

Street Commune. [Photo courtesy Chuck Gould]

Photo by epn

Screenshot from NOWSREAL with Peter Berg interacting with Holy Hubert on City Hall

steps at a Free City Noon Forever rally. (1968)

1% Free poster pasted on outside of a Haight Street storefront (1968).

The Free City Bank announcement. (1968)

Digger sheet "Term Paper" with reference to Gregory Corso's poem POWER. (1967)

Portion of Gregory Corso's poem POWER (from BIG TABLE_1, edited by Irving

Rosenthal, 1959).

|